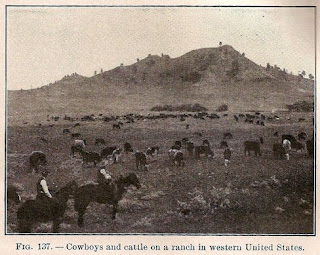

A look at cattle ranches of America's Great Plains, 100 years ago

The following paragraphs are quoted from the textbook, World Geographies: Second Book (p. 112-115) by Ralph S. Tarr and Frank M. McMurry, published in New York by the MacMillan Company in 1922. MEANING AND EXTENT OF THE GREAT PLAINS

Passing westward from the fertile valley of the Red River of the North, one finds the farmhouses decreasing in number and the country becoming more and more arid until finally, in western North Dakota, there is very little farming without irrigation. At the same time, the plains gradually rise higher and higher, until, near the base of the Rocky Mountains, an elevation of fully a mile above the sea is reached. This arid plateau, extending from Canada to southwestern Texas is commonly known as the

Great Plains...

...[M]ost of the arid region of the Great Plains is unsuited to farming. For this reason, there are comparatively few large cities, as you can see on the map. The entire western third of North and South Dakota, Nebraska, and Kansas, as well as the Great Plains farther west, are given over mainly to

ranching.

This industry is carried on in much the same way throughout all parts of the arid West. In western North Dakota, for instance, there is little water except in the widely separated streams, and there are very few trees except along the stream banks. Since the ranchman must have both water and wood, he locates his house, sheds, and stockades, or

corrals, within easy reach of these two things. If there is no neighbor within several miles it is all the better, for his cattle are then more certain to find abundant grass.

WHY FEW FENCES

Few fences are built, partly because most of the region is owned by the government, not by ranchmen. Very often they own only the land near the water; but this gives them control of the surrounding land, for it is of no use to anyone else if his cattle cannot reach the water. Another reason why fences are not common is that it is necessary for the cattle to roam far and wide in their search for food. The bunch grass upon which they feed is so scattered that they must walk a long distance each day to find enough to eat.

A single ranchman may own from ten to twenty thousand head of cattle, and yet they may all be allowed to wander upon public land, called "the range". Usually they keep within a distance of thirty miles of the ranch-house; but sometimes they stray one or two hundred miles away.

Twice a year there is a general collection, or

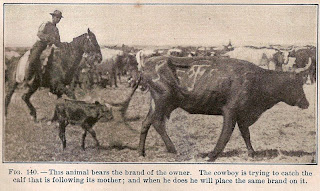

round-up, of cattle,-- the first round-up occurring in May or June, and the other early in the fall. One object of the first is to brand the calves that have been born during the winter.

Since there are few fences, cattle belonging to ranches which are even a hundred miles apart become mixed during the winter; and those in a large herd may belong to a score of different ranchmen. Each cattle owner has a certain mark, or

brand, in the form of a letter, a cross, a horseshoe, etc., which is burnt into the side of every calf.

A round-up, which lasts several weeks, is planned by a number of ranchmen together. A squad of perhaps twenty cowboys with a wagon and provisions, a large number of riding horses, or "ponies," and a cook, go in one direction; and other wagons, with similar "outfits," set out in other directions. Before separating in the morning, the members of a squad agree upon a certain camping place for the night, and they then scour the country to bring the cattle together, riding perhaps sixty or eighty miles during the day.

Each ranchman knows his own cattle by the brand they bear; and since the calves follow their mothers, there is no difficulty in telling what brand shall be placed on them. After branding the calves, each ranchman drives his cattle homeward to fend during the summer within a few dozen miles of their owner's house.

SECOND ROUND-UP AND WHAT FOLLOWS

The second large round-up is similar to the first, except that its object is to bring together the

steers, or male cattle, and ship them away to market; it is therefore called the

beef round-up. A ranchman who owns twenty thousand cattle may sell nearly half that number in a season. As the steers are collected, they are loaded upon trains and shipped to distant cities to be slaughtered.

Very often the cattle have found so little water and such poor pasturage, that they have failed to fatten properly, and must be fed for a time before being slaughtered. This may be done upon the irrigated fields near the rivers in the ranch country; or the cattle may be sent for this purpose to the farms farther east, as in Kansas, Missouri, Iowa, and Nebraska.

LIFE OF THE RANCHMAN

The lives of ranchmen and cowboys are interesting and often exciting, most of each day being spent in the saddle. They are so far separated from other people that they must depend upon themselves far more than most people do. For instance, a ranchman must build his house, kill his beef and dress it, put up his ice, raise his vegetables, do his blacksmithing, find his fuel, and even keep school for his children if they are to receive an education. He affords a good example of the pioneer life which was so common in early days.

This passage is quoted from the textbook, World Geographies: Second Book (p. 112-115) by Ralph S. Tarr and Frank M. McMurry, published in New York by the MacMillan Company in 1922.