Making hay in the Nebraska Sandhills, 1960s

Ranchhand resting on haystack. March, 1940, Dangberg Ranch, Douglas County, Nevada. Rothstein, Arthur, 1915- photographer. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA-OWI Collection, LC-USF34-029989-D DLC.

Ranchhand resting on haystack. March, 1940, Dangberg Ranch, Douglas County, Nevada. Rothstein, Arthur, 1915- photographer. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA-OWI Collection, LC-USF34-029989-D DLC.I followed a link to the blog of Montana's Prairie Mary and read an interesting post titled "The Scent of Hay". I wrote a long comment there about hay stackers and hay stacks which started to look a blog entry, so I decided to stop writing there and continue my remarks here.

Here's what I wrote on her blog:

There are many references in the pioneer literature to the sweet fresh scent of a freshly-stuffed hay mattress.

I wondered, Mary, if the "beaver slides" you mention are the same as the "slide stacker" where a load of hay is pulled by cables and pulleys to the top of a triangular frame and dumped? The "buck" on which the hay rides is lying flat against the stacker's frame in the photo at this link.

When I was a child in Nebraska, we stacked hay with a similar contraption. In the old days, the load was pulled to the top by horses and they were called "the stacker team". In my day, a tractor was used to pull the load up, but the person who drove it was still said to drive "stacker team".

After the haystacks were made, the next big job was to get them off the meadow. They were drug to a stackyard, usually at the corner of the meadow, to await the day that they were fed to cattle. A well-made haystack withstood moving, but a poorly constructed one would fall apart.

Eventually, haymaking went to mostly square bales, and now I see a lot of big round bales when I visit the area.

I did a little research after writing the remarks above and answered my own question. Yes, "beaver slides" and "slide stackers" are the same piece of hayfield equipment. And yes, this is the same type of haystacker that we used when I was a child in the Nebraska Sandhills.

The first step in making a haystack was mowing the grass. When the grass was dried by the sun ("cured"), it was gathered into long windrows by a dump rake.

Then the sweep ran down each windrow and gathered the hay in a big bunch. The sweep was a tractor with its steering, transmission, and seat switched around so the big wheels were in front. It had a large "buck" mounted on the front (formerly the back) of the tractor. The buck was a rack of long wooden prongs ("teeth") that slid under the windrow to gather the hay into a big pile in front of the tractor.

The sweep pushed the load of hay to the stacker and onto the stacker buck. The stacker buck was much like the sweep buck -- a rack of long wooden teeth. With an arrangement of pulleys, the loaded stacker buck was then pulled to the top of a triangular frame and the hay was dumped into the stacker cage.

In the cage, the hay was leveled and packed by a man with a pitchfork. It was very important to get the hay firmly and evenly packed so that the stack would remain standing when the stacker cage was removed. It was also important to create a rounded top on the haystack so it would shed water.

In the hayfield, my father always ran the sweep because it was the command position. From there, he controlled the tempo of the work. The rake was kept busy providing him with windrows to sweep up, and the stacker was kept busy by the loads of hay he brought to it.

The long wooden teeth on the sweep were polished by the hay to an ultra-smooth, shiny finish that was pleasant for a child to stroke. Sometimes a tooth jammed into the ground and broke, and haymaking came to a halt until the tooth was replaced. New teeth were pre-shaped into a point at the factory, but they felt rough and splintery compared to those that had been in use for a while.

The most dangerous job in the hayfield was making the haystack. When the big heavy load of hay whizzed up the slide and shot into the cage, a careless hayhand could be buried or knocked off the stack if he wasn't safely out of the way. It was also a very hot, dirty job that required stamina and strength.

My own grandfather, Ralph Hill, broke his back somehow in a haystacker accident. I am not sure if he fell from the top of the stack, or if he was knocked off it by a load of hay. Perhaps someone in my family will tell me exactly how the accident happened. I believe he had climbed up there to help the hired man. At any rate, he was left partially paralyzed from the accident, a man in his 30's with a ranch to run and a family to provide for. Much responsibility fell on my father, the oldest son, from that day on.

I am sure that my grandfather's accident as well as efficiency in the hayfield played a part in my father developing a hayfield innovation that eliminated both the man in the stacker cage and the man at the stacker team. My dad welded a large tower onto an old truck chasis. The tower was positioned by the stacker cage, and a man on the tower brought the load of hay up the stacker slide and dumped it in the cage by remote controls and then used a hydraulic arm and hand to pack the hay into the haystack.

My father once commented that when he was a boy, it took a team of six or eight horses to pull a load of hay up the stacker, and there they stood all day, all that horseflesh for that one job. How glad they were, he said, to put a tractor to the stacker team position. Later, his invention reduced the stacking job to just one person.

Mowing was my job in the hayfield. I inherited this job from my mother. When we were little girls, she helped with the mowing. When I got old enough to drive a tractor, I helped with the mowing which kept me out of trouble and allowed my mother to do other things such as cook for the hay crew, ride the pastures to check on the cattle, and run to town for machinery parts.

When I first started mowing, I drove a little Allis Chalmers CA with a mowing machine that had a six or seven foot bar. I honestly think it was just a six foot bar.

I was the secondary mowing person. Don Saar, our hired man, was the primary mowing person and he had a double bar mower that cut a swath of 15 feet or more. My little mowing rig was fairly reliable about breaking down every afternoon at 4 p.m., so I usually got to go home early from the hayfield.

The next year, my dad bought a new 9-foot mower for me, and it didn't break down so I had to stay in the hayfield all day after that. A few years later, he bought a New Holland windrower, a big self-propelled machine that cut the hay, crimped it to accelerate the curing, and kicked it out into a windrow. When we got that machine, I became the only person mowing and I learned a lot about responsibility.

Mowing was a solitary job, and I had a lot of time to meditate while steering the machine down the edge of the uncut grass. Still, I had to pay enough attention to avoid leaving streaks of uncut hay from careless steering or from failing to notice that a clog of grass had developed on the mower bar. My dad hated streaks.

Making hay is the most important thing a rancher does every summer, because it's the winter food for the cattle. We had fine "sub-irrigated" hay meadows along the Skull and Bloody Creeks in Duff Valley, and I don't think our hay crop was ever poor enough that we had to buy hay. The hay meadows around Newport, Nebraska (in the same county that I grew up) are some of the finest in the world.

Truly, the bounty of the prairie is its grass.

I know y'all have been pining to know exactly what I mean in my profile when I state that I like "any piano boogie-woogie."

I know y'all have been pining to know exactly what I mean in my profile when I state that I like "any piano boogie-woogie."

Unfortunately, our yard has a lot of

Unfortunately, our yard has a lot of  I think I had many dreams, but I remember only a single scene. I was wearing knee-high leather boots and I was spreading steak sauce on them as I sat on a park bench in the cemetery. I assume that had something to do with the headache or perhaps Fox News.

I think I had many dreams, but I remember only a single scene. I was wearing knee-high leather boots and I was spreading steak sauce on them as I sat on a park bench in the cemetery. I assume that had something to do with the headache or perhaps Fox News.

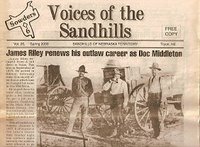

I wrote a post several weeks ago about

I wrote a post several weeks ago about