My brother's cattle dogs

Jimmy is a Border Collie. He's the younger of my brother's two cattle dogs. Both dogs are intensely attached to my brother, and they aren't friendly with strangers. They consider it their duty to protect their people --it's a characteristic of their breed.

I really felt honored when Jimmie let me pet him on the last day of my recent visit to my brother's ranch in Kansas. Hank, the older dog, would not make friends with me. When I took the photo below, Hank knew I was looking at him with my camera, so he carefully ignored me.

I think Hank is also a full-blooded Border Collie, but I could be wrong. A cow kicked Hank a few years ago and broke his leg. After several surgeries, his bad leg still bothers him. He can't run as fast or jump as well as he used to, but he still likes to help.

Hank and Jimmy love to go for an adventure. Here they are in the back of the truck. When my brother goes to the pastures to check his cows, they ride in the back of the 4-wheeler.

As soon as they enter the pasture, Jimmy jumps out and runs. Pretty soon, my brother asks Hank if he wants to run too, and he usually does. The dogs run in front of the 4-wheeler and smell all the important places along the trail. Many sites need pee from both dogs. They also check certain clumps of bushes for rabbits and deer every day. A good chase is remembered forever.

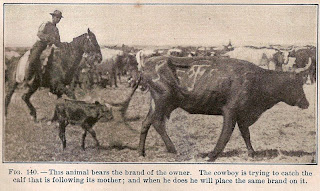

One evening while I was there, we found the neighbor's bull in the pasture with my brother's cows. The dogs saw him immediately and knew that he did not belong there. Here's Jimmy, heading the bull down the road to another pasture.

My brother commented that this bull seemed accustomed to being driven by dogs, because he didn't fight Jimmy much. Still, the bull didn't really want to leave the cows. My brother put the 4-wheeler between the bull and the dog a few times when the bull put down his head and charged at Jimmy. It made me nervous.

Here we go over the hill and across the pasture with the bull. When we got to the corner of the pasture, one of my brother's bulls spotted the stray and headed toward us. The situation could have turned ugly, but my brother got the gate open while the dogs held the red bull, and we got the red bull through the gate and into the corral before the black bull arrived. They bellowed fiercely, but two fences were separating them.

I admired and respected the nerve of the cattle dogs, and I said so to my brother. Oh, he said, things like that are what the dogs live for.

A ride around the pasture fences revealed no broken wires, so the stray bull's method of entry into my brother's pasture remained a mystery. We had seen him on the road earlier in the day. My brother speculated that the bull might have walked across or jumped across the cattle guard. (Some cattle learn to do that.) Or someone might have put him in the pasture to get him off the road. The poorly-kept fences around the bull's home pasture are teaching him to be "breechy" --that is, good at (and fond of) going over, under, around, and through fences.

Every pasture ride with the dogs ends with a race. My brother backs up to a little high spot so Hank can jump into the back of the 4-wheeler (he has the bad leg). Then Jimmie takes off like a greyhound, and my brother drives fast on the 4-wheeler behind him. Hank barks wildly with the excitement of chasing Jimmy, and Jimmy wins the race. Riding along is an exhilarating experience.

My brother says his dogs listen to everything he says and are always thinking about what he means. They don't always understand, but they always want to understand. They have large vocabularies and excellent memories. They love him, and he loves them. They love my sister-in-law too, but my brother is their favorite and, in their eyes, the esteemed leader of their pack.

I can't write about my brother's dogs without mentioning Sammi, his first cattle dog. She was a sweet, smart Australian Shepherd - Border Collie mix. She helped my brother train Hank, her successor. I showed my son this photo of Sammi's grave tonight, and I may have seen a tear in his eye. Sammi was dearly loved by my children, and she lives on forever in their memories of childhood visits to the ranch.