A Confederate States Army camp near Hopkinsville during the Civil War

I've mentioned before that

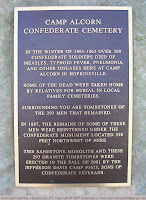

Riverside Cemetery in Hopkinsville, Kentucky, is the final resting place of about 300 Confederate soldiers who died of measles, dysentery, tuberculosis, pneumonia, typhoid, and other illnesses while camped at Camp Alcorn during the Civil War.

I was quite interested when I stumbled across some correspondence to, from, and about Camp Alcorn in an old book that has been digitized by Google.

The book is

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. It was published in 1902 by the U.S. Government Printing Office, with input from many authors and sources, including the United States War Dept, United States Congress. and the United States War Records Office.

I've written the following brief history of Camp Alcorn based mostly on Confederate letters that are recorded in this book...

How Camp Alcorn was established

After a number of skirmishes with Union troops in this part of Kentucky, Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston and Brigadier General Felix Kirk Zollicoffer took Bowling Green in the fall of 1861. Meanwhile Confederate General Simon Buckner occupied Hopkinsville.

These victories led to a Confederate plan to create a "Kentucky Line." The idea was to stop the Union forces in Kentucky, and thus to prevent the Union from gaining control of rivers and railroads that led to Nashville, Tennessee, and beyond. Also, there were iron furnaces of importance to the Confederacy along the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers of western Kentucky.

Shortly after taking Hopkinsville, General Buckner was promoted and moved to Central Division of Kentucky headquarters to Bowling Green. Buckner left Brigadier General J. L. Alcorn in camp near Hopkinsville with a brigade of Mississippi volunteers and two small regiments. Alcorn had brought these troops from Mississippi as part of a response from that state to a request for 10,000 men for sixty days service in Kentucky.

Alcorn was supposed to defend the Cumberland River and the railroad bridge over it at Clarksville, Tennessee, from an overland attack from the north/northeast. However, widespread illness among his soldiers limited his ability to do this job.

General Alcorn returns to Mississippi after escorting the troops to Kentucky and setting up camp at Hopkinsville

On October 19, 1861, Alcorn wrote to General Buckner, to give a scouting report and to inform him of the health situation in camp.

My command, after furnishing nurses for the sick, is reduced to a battalion. It appears that every man in my camp will directly be down with measles. The thought of a movement in my present condition is idle. I am not more than able to patrol the town.

Source: Letter from Alcorn to Buckner, Oct. 19, 1861 (pp. 464-465)

At the end of the letter, he requested to be relieved of command at Hopkinsville so he could return to Mississippi.

[T]he cause for my continuance no longer exists in force sufficient to detain me. I wish to leave for Mississippi; and ask your permission to fix the 27th instant as the day for my departure. This post is an important one, and should not be commanded by one who has not the confidence or is distasteful to the Government at Richmond. My service as brigadier-general of Mississippi is due that State only. If the Confederate Government wished me, I would be appointed. This not being done, I am an intruder. My self-respect, my own honor, is dearer to me than country or life itself. The hope of being able to make an early movement has lured me; that hope dissipated, common decency requires me to leave this command. Besides, to stay here and labor and toil as I do, struggling with disease and death, to be superseded presently, or, if continued, to be a mere interloper, a nondescript, every impulse of my nature says, "No; death first," My command will complain, but this will soon be hushed, for now they are bound. I shall leave with them my son, a captain of a company, as hostage that my heart is with them.

In conclusion, I thank you most sincerely for the kind manner in which you have treated me since my return to my native heath, and beg that you will have some one to take my command, if not before, on the day indicated. Do not neglect this, I beg you.

Source: Letter from Alcorn to Buckner, October 19, 1861 (pp. 464-465)

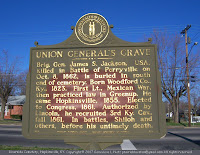

My research leads me to believe that General Alcorn survived the war and later became a U.S. senator from Mississippi.

General Tilghman assumes command and learns of conditions at Camp Alcorn

Shortly after Alcorn requested permission to go home, Brigadier General Lloyd Tilghman was assigned to command the troops at Camp Alcorn. Tilghman was a West Point graduate from Baltimore, Maryland, and a civil engineer by trade. He had served in the Mexican War and had helped to build the Panama railroad. Railroad construction brought him to Paducah, Kentucky, and in the 1850s, he built

a home there that you can still visit today.

When General Tilghman took over Camp Alcorn, the men were apparently living in very sad conditions. He wrote to General Johnston at Bowling Green on October 27, 1861:

I have been detained here [at Clarksville, Tennessee] to-day, preparing matters to aid my organization at Hopkinsville, where I learn a vast deal of suffering exists, owing to the exposed condition of men. I have made arrangements to put 200 women to work on clothing, and hope for a contribution of blankets and clothing from the society at this place. I regret deeply to hear of the condition of things at Hopkinsville, but hope to overcome them. I am sorry also to hear of the inefficient condition of things at Fort Donelson [along the Cumberland River, west of Clarksville, Tennessee). I fear our interests there are well-nigh beyond our control.

Source: Letter from Tilghman to Johnston, October 27, 1861 (p. 479)

Reports from Hopkinsville by General Tilghman

By the 29th of October, General Tilghman had arrived in Hopkinsville. He reported the following to Bowling Green:

I had hoped that the picture, sketched to me of matters here might not have been realized, but I am compelled to think it not too highly colored. Under all the circumstances, 1 doubt not General Alcorn has made the best of things, his camp being merely one large hospital, with scarce men enough on duty to care for the sick and maintain a feeble guard around them, with insufficient pickets at prominent points. Over one-half the entire command are on the sick list, with very grave types of different diseases. Those remaining and reported for duty leave not enough really well men to do more than first stated. The Kentucky Battalion of Infantry, numbering 547, have only 45 cases reported sick. The measles have made their appearance, and the battalion will average 20 new cases per day, judging from to-day's report. The morning brigade report, herewith inclosed, shows only 716 for duty out of a total of 2237.

Source: Letter from Tilghman to Col. W. W. Mackall, October 29, 1861 pp. 485-486

On November 2, General Tilghman wrote again to Bowling Green:

You will have some idea of [the situation in Hopkinsville] when I tell you that in endeavoring to get up a little command last evening to move on Princeton, 1 found that the First Mississippi had 151 for duty, the Third 128. Out of these, guards and pickets had to be taken, giving me only 100 men from each regiment, half of whom were really unfit for the night march (raining in torrents). I managed, however, to get together 400 men and two pieces of artillery, the poorest clad, shod, and armed body I ever saw, but full of enthusiasm. I soon found that half the infantry were so unfit, that the surgeon stated that humanity demanded they should not go. I was relieved by a courier from my embarrassment and delayed until this morning, when a second courier relieved me entirely, by stating that the enemy had turned off from Princeton and [were] making northward. This morning I learn again that they have retired again (as their gunboats have done) towards the mouth of the river. You may therefore consider me relieved of the pressure for a few days.

Source: Letter from Tilghman to Buckner, November 2, 1861 (p. 500)

On November 7, 1861, reinforcements arrived -- volunteers from Texas led by John Gregg. They were partially armed and not yet organized into a regiment. Gregg wrote the following to command in Bowling Green:

Except a number of sick men on the road our nine companies are all here. The number is 749. Five of our number died on the way. From exposure to cold and wet on our journey we have more coughs and colds than I ever saw among the same number of men. Under General Tilghman's direction we will organize and elect our officers to-day or to-morrow. We have the consent of the Secretary of War to that purpose.

Source: Letter from Gregg to Mackall, November 7, 1861 (p. 524-525)

Health at Camp Alcorn improved under General Tilghman's command

By November 11, 1861, General Tilghman was a bit encouraged about the health of the camp. He wrote the following along with a long report of scouting and skirmishes north of Hopkinsville:

I am glad to be able to report "improvement" in my whole command, and the gradual assuming of form and energy in every department. A thorough change in my entire hospital arrangement, by the use of appropriate buildings and the procurement of proper supplies, aided by thorough police, has produced the results usually attainable through such means. The cheerful and able assistance rendered me by those of my own staff, as well as many of the regimental officers, is deserving of high commendation. The command, however, is yet very insufficient for the objects I know you would desire to have attained, and as it seems my only hope is in a patient waiting for re-enforcements, I can only hope I may now be allowed a little respite from the constant danger, real, that has surrounded me for the last ten days.

Source: Letter from Tilghman to Mackall, November 11, 1861 (p. 535-537)

At the end of this letter, he asked that funds for clothing be allocated immediately for the troops under his command.

The First Presbyterian Church of Hopkinsville was one of the sites used as a hospital during the winter of 1861-62, according to a historic marker at the church (corner of 9th and Liberty.)

General Tilghman's letter of November 13 to Bowling Green contained a mixture of good and bad news. A batallion of Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest's cavalry had arrived from Fort Donelson. The forested area around the river was not good for cavalry maneuvers and furthermore, there wasn't enough food for the horses. General Tilghman had already sent out a joint cavalry and infantry group to prevent Union theft of a large herd of pigs that had been purchased by the Confederate agent in Clarksville. Tilghman also wrote, "My command still improves; are getting into their new hospitals." Source:

Letter from Tilghman to Mackall, November 13, 1861 p. 549)

General Tilghman transferred to Forts Henry and Donelson

On November 14, orders were issued by General Buckner in Bowling Green, transferring Brigadier General Tilghman to the Cumberland River. He was given command of Forts Donelson and Henry, where a dangerous lack of discipline and organization existed, even as the Union was getting new and better gunboats. A Brigadier General Charles Clark was put in command of the two Mississippi batallions at Hopkinsville.

This is the end of the Camp Alcorn paper trail I've been following. I can add that General Tilghman did his best in December, 1861, and January, 1862, to get the troops and fortifications at Fort Henry and Donelson ready for battle. The Union attack came in February, 1862 -- 15,000 Union troops and seven Union gunboats -- and both forts fell into Union control, opening the way to Clarksville, Nashville, and beyond. It was the first big Union victory of the war.

General Tilghman surrendered with his men and was imprisoned for about six months. After he was released in a prisoner exchange, he rejoined the Confederate forces in Mississippi. He died in battle at Vicksburg, Mississippi, in 1864, and it is reported that

his men wept when he fell.

The end of Camp Alcorn

As for Camp Alcorn, some of the sick were sent to a Confederate hospital in Clarksville, Tennessee, in November due to the likeliness of a Union attack upon the camp. 53 of Camp Alcorn's volunteer Texans died in Clarksville, and I am not sure how many others.

A historic marker at Riverside Cemetery states that Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest lived in a log house in Hopkinsville with his wife and daughter during the winter of 1861-62 and withdrew from Hopkinsville to Tennessee when the CSA left Bowling Green.

Kentucky's historic markers document a busy winter of raids and reconnaissance by Forrest in the area around Hopkinsville, though many of his men fell sick while camped here.

Camp Alcorn was apparently broken up when all its able-bodied troops were sent to the defense of Fort Donelson in February of 1862. As far as I know, the only remaining evidence of its existence at Hopkinsville is the Camp Alcorn cemetery.

A local Sons of Confederate Veterans group (

Jefferson Davis Birthplace Camp # 1675) has worked hard to honor these fallen Confederate soldiers by compiling records, providing individual tombstones for each known soldier, and faithfully placing flags for them.

Related articles on this blog

Civil War Graves at Riverside Cemetery in Hopkinsville, KY

A Walk In Riverside Cemetery

More About Riverside Cemetery

Letters sent from Camp Alcorn

From a Confederate soldier to a lady he admired

Description of the sickness at Camp Alcorn and the weather, Winter of 1861-62

Related articles on this blog

Civil War Graves at Riverside Cemetery in Hopkinsville, KY

A Walk In Riverside Cemetery

More About Riverside Cemetery

Letters sent from Camp Alcorn

From a Confederate soldier to a lady he admired

Description of the sickness at Camp Alcorn and the weather, Winter of 1861-62 (Scroll down to "Letter from the 'Bass Grays'.”)

A description of the housing at Camp Alcorn

Additional related material:

That Dark and Bloody Ground: The Kentucky Campaign of 1861

One Camp Alcorn soldier's history

Tribute to General Lloyd Tilghman

Norwegian reenactment group for the

7th Texas Infantry, includes a list of all soldiers who died at Camp Alcorn

Lloyd Tilghman at Wikipedia

Tilghman monument at Vicksburg

Another photo of Tilghman monument

Captain J. M. Sparkman's Tennessee Light Artillery Company

My Civil War, Before, During, and After -- Memoirs of a Union soldier who fought in this part of Kentucky with the 5th Iowa Cavalry